Compiling fast GPU kernels

Bringing support for Nvidia and Apple GPUs to Luminal through compilers

Image Credit: https://exxactcorp.com/

Luminal compilers can now generate CUDA and Metal kernels on the fly, yielding specialized GPU compute for each model.

In our day-to-day lives most computing is done on general purpose CPUs. The combination of ubuquity and flexibility makes them an attractive option for most software. However, certian types of software like graphics are very compute-intensive, and since CPUs execute a single stream of instructions they have very little (or no) parallelism, leading to slow performance and high power usage.

As graphics improved in the 80s and 90s, especially with the onset of 3D graphics, specialized hardware was required to render complex scenes at reasonable speed. Companies like Nvidia began releasing specialized chips able to do massively parallel compute, which served graphics applications well since individual pixels tend not to depend on other pixels.

Fastforward to the 2010s, neural networks were getting bigger. The true innovation behind the famous AlexNet wasn’t the architecture or even the data, but the development of efficient GPU code capable of training far larger models than anyone else.

Today, nearly all ML workloads are done on GPUs or other more specialized hardware.

GPU Kernels

So how do we actually program these chips? Do they run normal assembly we can compile to from the langauges we already use? Unfortunately not. Hardware manufactureres have created custom languages programmers use to write little programs that get parallelized on the hardware called kernels.

An example kernel to do many additions in parallel on Nvidia GPUs might look like this:

__global__ void kernel(float *out, const float *a, const float *b) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

out[idx] = a[idx] + b[idx];

}

In this kernel we have 2 inputs, a and b, which are float arrays. We get the index of the current thread using blockIdx, blockDim, and threadIdx, and use that to index into the input and output arrays.

This kernel gets ran for each element of the input arrays, all in parallel.

Compiler flow

The typical approach in Luminal for supporting new backends would be:

- Swap out each primitive operation with a backend-specific operation.

- Add in operations to copy to device and copy from device before and after Function operations.

- Pattern-match to swap out chunks of operations with specialized variants.

- All other optimizations.

Since we looked at a CUDA kernel above, let’s go through how we do this for the Metal backend to support Apple GPUs.

Step 1: Metal Primops

We want to generically support all possible models in Luminal, so our first step is to replicate all primitive operations with a Metal version. Since there are 11 primitive operations, we need 11 Metal ops. You can see these in crates/luminal_metal/src/prim.rs. The compiler simply loops through all ops in the graph and swaps them out with the Metal variant.

These primitive operations are very simple. Here’s the MetalExp2 op, slightly simplified for clarity:

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct MetalExp2<T> {

...

}

impl<T: MetalFloat> MetalExp2<T> {

pub fn new() -> Self {

let type_name = T::type_name();

let code = format!("

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

kernel void mkernel(device {type_name} *inp [[buffer(0)]], device {type_name} *out [[buffer(1)]], device int& n_elements [[buffer(2)]], uint idx [[thread_position_in_grid]]) {

if (idx < n_elements) {

out[idx] = exp2(inp[idx]);

}

}");

Self {

pipeline: compile_function("mkernel", &code),

...

}

}

}

impl<T> MetalKernel for MetalExp2<T> {

fn metal_forward(

&self,

inputs: &[(&Buffer, ShapeTracker)],

command_buffer: &CommandBufferRef,

output_buffers: &[&Buffer],

) {

let inp_size = inputs[0].1.n_elements().to_usize().unwrap();

let encoder = command_buffer.compute_command_encoder_with_descriptor(ComputePassDescriptor::new());

encoder.set_compute_pipeline_state(&self.pipeline);

// Set function inputs

encoder.set_buffer(0, Some(inputs[0].0), 0);

encoder.set_buffer(1, Some(output_buffers[0]), 0);

encoder.set_u32(2, inp_size as u32);

// Execute

encoder.dispatch_1d(inp_size);

encoder.end_encoding();

}

}

Step 2: Moving data around

Since our data always starts on the host device (normal RAM), we need to move it to GPU memory. This means we need to look at the remaining ops that produce data from the host, and insert a CopyToDevice op, and look at where we need to get data back to host and insert a CopyFromDevice op.

In our case, the CopyToDevice simply makes a MetalBuffer that points to the memory our data is already in. Since Macs have unified memory, no actual copying gets done here. Likewise, in the CopyFromDevice op, we’re just creating a new Vec with the buffer’s pointer. No actual copying needs to happen.

Step 3: Custom ops

Certian patterns of ops are very performance intensive, so we want to swap in an efficient version for each pattern in the graph. Matmul is a good example of this. Matrix multiplication is perhaps the single most compute intensive operation in neural networks, so we want to make sure it’s done efficiently. There’s an optimized Metal matmul kernel we swap in every time we see the Broadcasted Multiply -> SumReduce pattern.

Note all of this is always done by pattern matching, not by matching explicit flags. So if a model has that pattern somewhere else in another layer, it can use a matmul even if the model author didn’t realise it was a matmul!

Step 4: Kernel Fusion

Now that we have all the specialized ops swapped in, we can do the fancy automatic compilation. For Metal, this involves first fusing all elementwise ops we see together into one kernel.

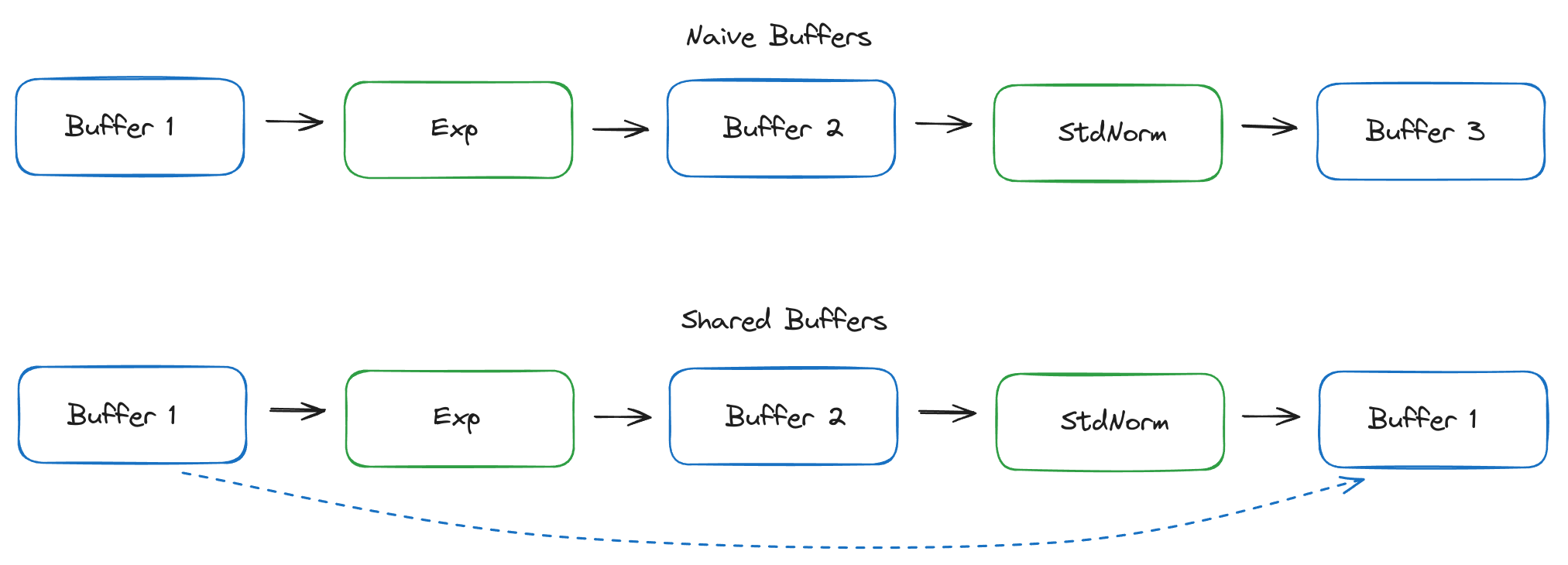

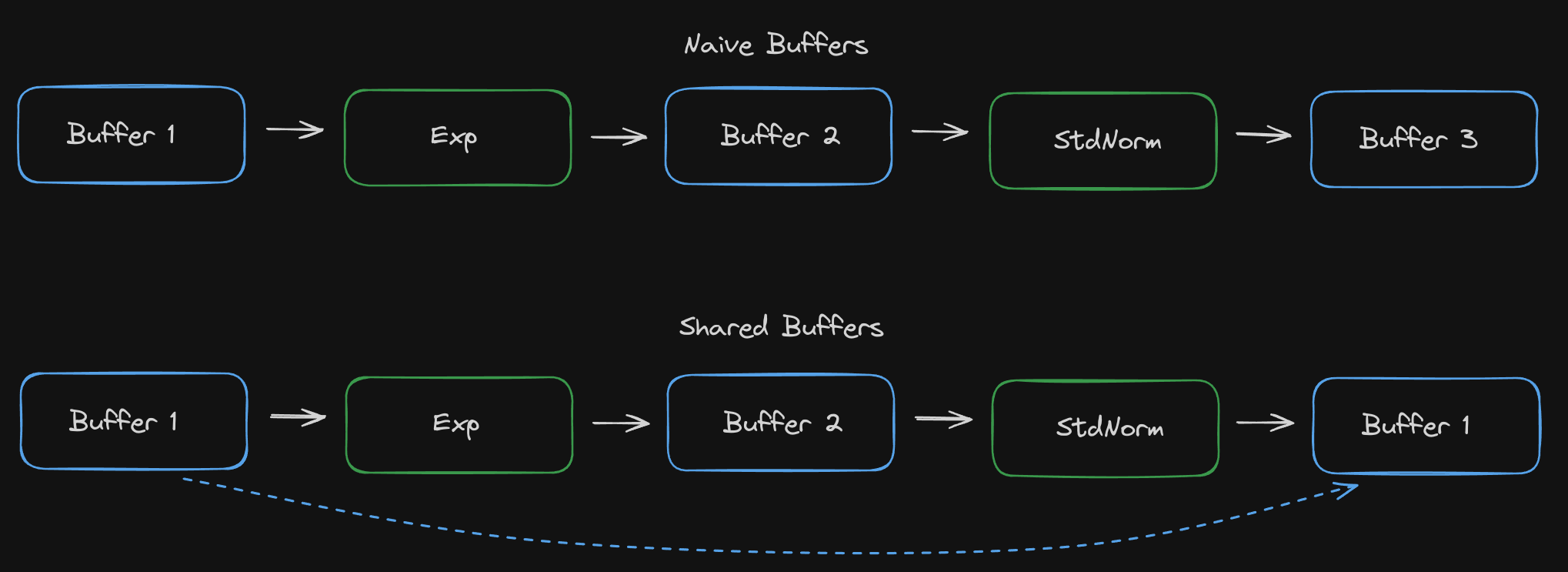

Let’s say you have a tensor a, and you want b = a.cos().exp(). Naievely we would allocate an intermediate buffer, launch a Cos kernel to do cos(a), write the output to the intermediate buffer, then launch an Exp kernel to do exp(intermediate) and write the result to an output buffer.

Elementwise fusion does away with that and generates a single kernel that does out = exp(cos(a)), so no intermediate reads and writes are needed, and only one kernel needs to be launched.

This actually is taken much furthur, fusing unary operations, binary operations, across reshapes, permutes, expands, etc. Turns out we can get very far with this idea!

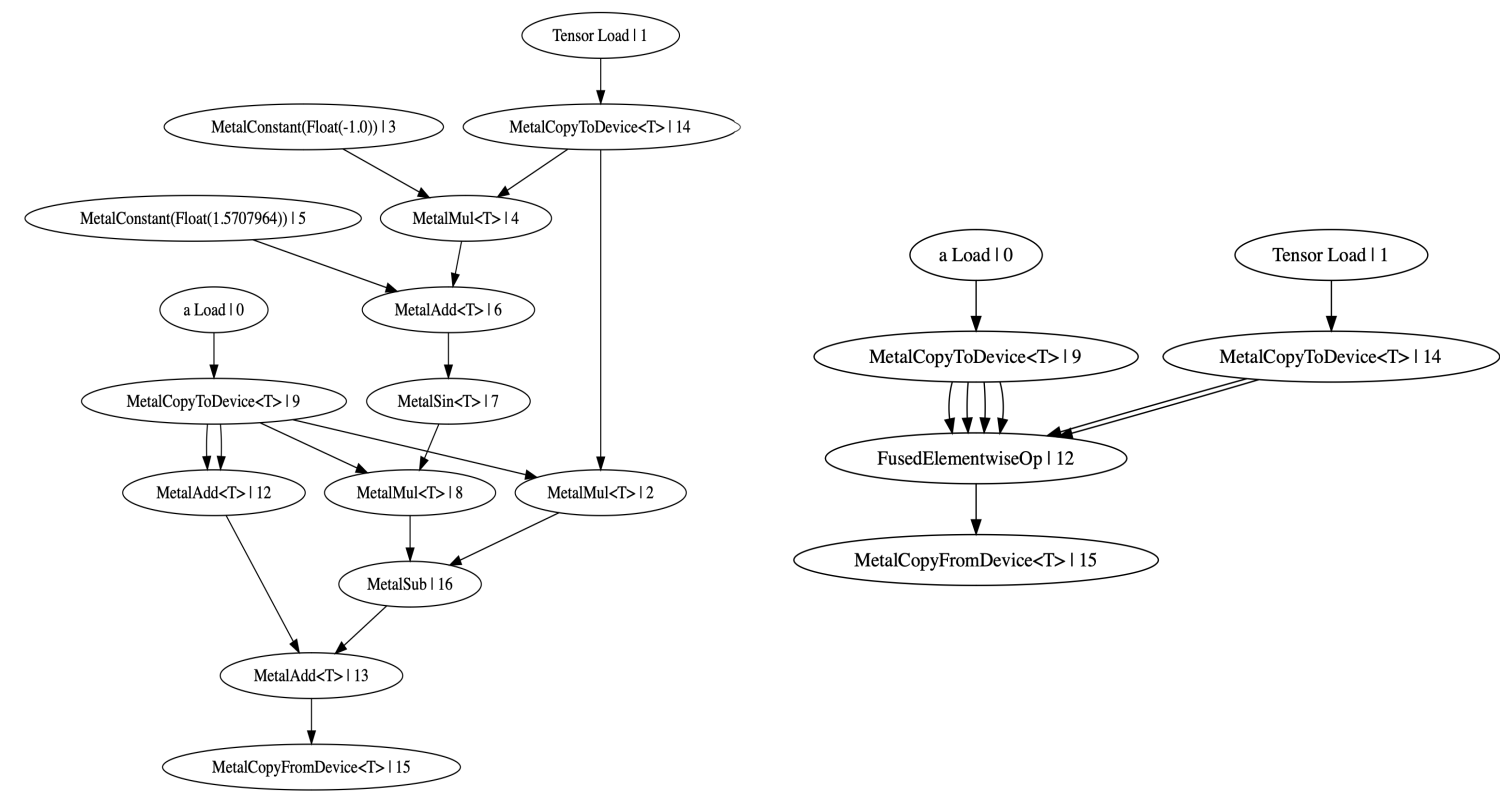

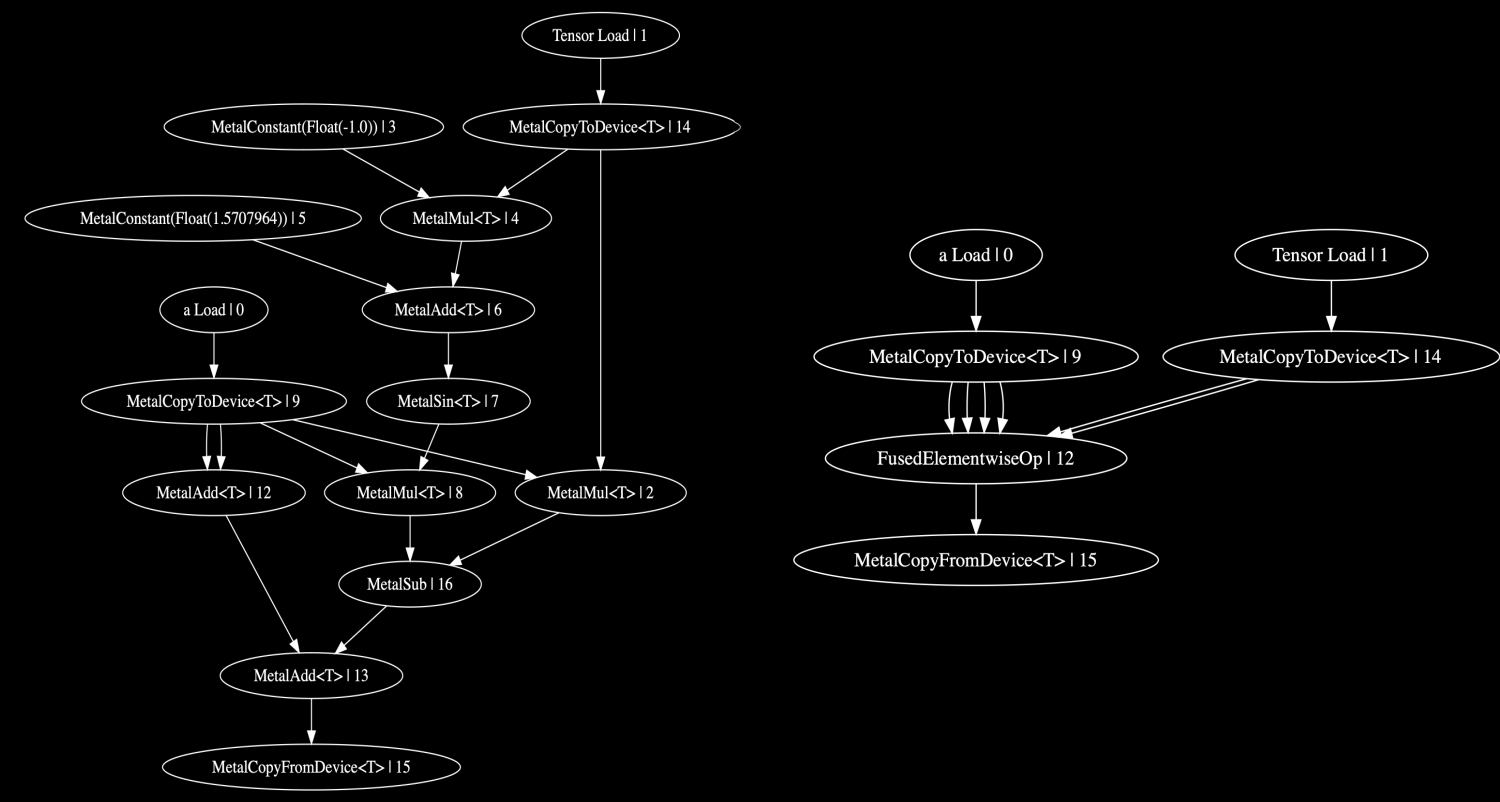

Here’s an example of how many ops fusion can merge together. On the left is the unfused graph, on the right is the functionally identical fused graph:

Step 5: Buffer Sharing

Storage Buffers

Since we’re reading buffers which may not be read again, it would make sense to re-use that memory directly. And since we know in advance how big all the buffers are, and when we’ll be using them, we can decide at compile time which buffers should be used where.

The Metal StorageBufferCompiler does just this, computes the optimal buffer assignments to minimise memory usage, and adds a single op at the beginning of the graph to allocate all required buffers once.

This op also keeps track of previously allocated buffers on earlier runs of the graph, and tries to re-use those buffers. Ideally each time a graph is ran, zero allocations need to happen!

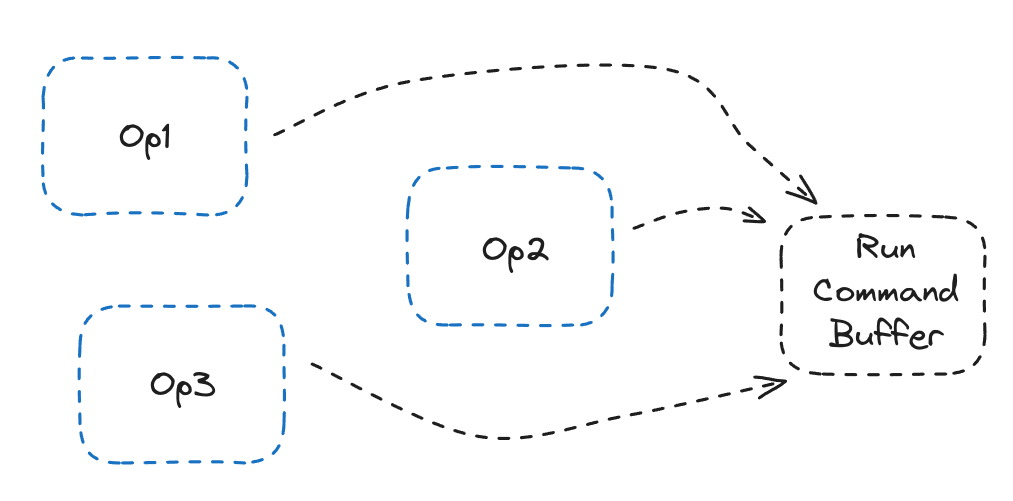

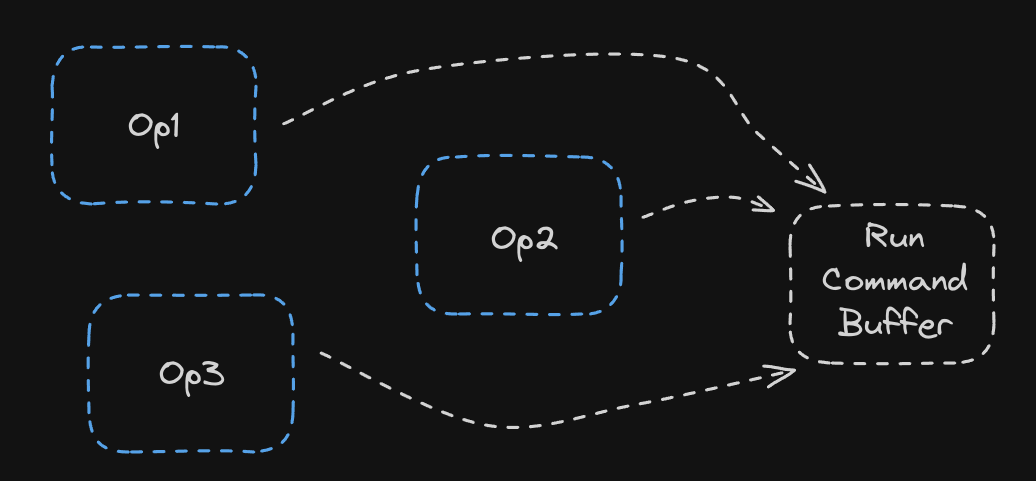

Command Buffers

Another important concept in Metal is the Command Buffer. This is where we queue all our kernels to run. Naievely we can simply run the command buffer after queueing a single kernel, and simply do that for each op we run. But running the command buffer has latency, transferring the kernel to the GPU has latency, and this is a very inefficient use of the CommandBuffer.

Instead, wouldn’t it be great if we can just build a massive command buffer with all of our kernels, with inputs and outputs already set up, and just run the whole thing at once?

That’s exactly what the CommandBufferCompiler does. It can create groups of ops to share the command buffer between, and run the command buffer only when we actually need the outputs. Usually we can put an entire model on a single command buffer. For instance, the entire Llama 3 8B uses just one command buffer!

What does this get us?

The great thing about Luminal is that since most complex things are done in compilers, to the user, the only change they need to make is swapping this:

cx.compile(<(GenericCompiler, CPUCompiler)>::default(), ());

with this:

cx.compile(<(GenericCompiler, MetalCompiler<f32>)>::default(), ());

or this:

cx.compile(<(GenericCompiler, CudaCompiler<f32>)>::default(), ());

and the model now runs on the GPU!

Wrapping up

This level of flexibility is only afforded to us because compilers can handle so much complexity internally, with correctness guarentees due to the simplicity of the graph.

One more note: The core of Luminal has no idea about any of this! GPUs are a foreign concept to it, which is nessecary since we want to add backends to TPUs, Groq chips, and whatever else may come in the future without changing anything in the core.

We’ll see this theme come up many times as we touch on datatypes, training, and large-scale distributed compute. The user shouldn’t have to worry about any of this, and using the complexity bottlenecks the graph provides, we can be confident these compilers are compatible with eachother and Just Work™.

We’re pushing deeper into the domain of frameworks orders of magnitude more complex, and adding new features like training, multi-modality and multi-GPU, so check out the repo and come join us on the Discord and build the future of ML together!